By Jerry Davis

Editor’s Note: We are honored to feature this insightful article by Jerry Davis. As a dedicated researcher, practitioner of De Campo 123 Original, and long-time student of the late Punong Guro Edgar Sulite, Jerry provides a comprehensive look into the deep historical and cultural currents that shaped GM Jose Caballero’s art. His perspective enriches our understanding and appreciation of De Campo’s unique place within Filipino Martial Arts.

First, some background: According to fossil evidence, hominids have lived in the Philippines for at least 1,000,000 years. From archaeological findings, modern humans have been there for at least 45,000 years. Multiple invasions of people from different cultural backgrounds have occurred over the last few thousand years, including Chinese, Malaysians, Indians, and Indonesians. These different groups have all left their mark in various ways. The islands have functioned as a barrier in some respects, leading to the development of many distinct cultural identities and languages spread across the archipelago.

The Crucible of History: The Philippines Before De Campo

Pre-Colonial Roots and Spanish Arrival

During the 1500s, the Europeans were expanding their influence worldwide, and a seminal event in Filipino history was the death of the Portuguese navigator, Ferdinand Magellan, at the hands of Lapulapu (Battle of Mactan) and his warriors off the island of Mactan near eastern Cebu, an island in the Visayas (central) Philippines. In 1565, the Spanish more or less conquered the Philippines, although “conquered” is a subjective word under the circumstances. The Philippines is divided into three basic areas: Luzon (north), Visayas (central), and Mindanao (south). Luzon was already well-settled with trading routes across the southeast, but Mindanao was (and still is) in a state of constant war with Indonesian Muslim pirates.

Hispanicization and Martial Necessity

Wherever the Spanish went, their basic strategy was to Hispanicize the people they encountered by indoctrinating them with Spanish culture, namely their business practices and the Catholic religion. By “business practices,” we mean exploiting local people and resources for the Spanish Crown. Their methods were often at odds with the Spanish religious authorities who were charged with converting the local populace to Christianity (as opposed to abusing or killing them). But the larger initial problem was the sparse number of Spanish soldiers and priests needed to control the shorelines, which were under constant assault from the Indonesian Muslims. Managing the central islands (Visayas) was also necessary to protect the northern islands (Luzon).

Eventually, the Spanish found they had to train the Filipino people who voluntarily accepted Spanish rule in martial techniques to protect the coast and stave off Filipino antagonists on the islands themselves. In general, the priests were well-versed in sword and knife techniques, teaching their Filipino converts how to defend themselves from the Muslims. They also arranged a series of forts along various coastlines where the Muslims were known to appear, usually at specific times during the year. The Spanish typically gathered the people at specific locations where they could Hispanize them as well as keep track of them.

From Colonization to Independence

Eventually, Spanish abuses undermined their colonization process. When the American government offered to help them get rid of the Spanish, they accepted with the provision that they would be granted their independence. In 1898, the Spanish were driven out of the Philippines, but then the Americans decided to keep it as a US territory, which created new conflicts with their new rulers. However, when the Japanese invaded the Philippines, they proved to be much worse than the United States, so the Filipinos once again joined with the Americans to drive out the new invaders. Eventually, after the war, on July 4, 1946, they were granted complete independence.

The System of GM Jose Caballero

A Confluence of Cultures

So how does all this tie into GM Caballero’s system? For one thing, the Philippines is the only majority-Christian nation in Southeast Asia, with a large majority of Catholics. Through the Spanish, they learned specific martial techniques verified from Spanish sword manuals of the 1500s–1600s that still exist. Because of a general absence of firearms and organized law enforcement, these techniques were transmitted down to modern times. In addition, the Spanish language proved to be more descriptive for some items and concepts than native languages, so much of the martial curriculum is adapted from Spanish. Furthermore, some of the more eclectic beliefs, like orasyon and anting-anting, are related to religious beliefs.

It’s unclear exactly what kind of native martial arts existed before the Spanish arrived, but it is well known that Chinese, Malaysian, Indian, and Indonesian arts influenced the development of Filipino martial arts. Aspects of these various arts can be seen in different Filipino systems across the FMA spectrum. Some have well-documented connections to other arts, but others can only be surmised by movements not commonly seen in FMA but common in other arts. And we know from archaeological and archival evidence that spears, bows and arrows, shields, and other martial hardware were used prior to the Spanish arrival.

In addition, the Filipinos were very impressed with the American educational system, upon which they based many of their schools and colleges. GM Caballero’s carefully constructed curriculum is a reflection of this influence, and sometimes English words find their way into some of the Filipino systems. Yet not all Filipino systems have clear constructs or connections with other countries or foreign nationalities, and often the historical data was lost or never existed in the first place. Oftentimes, the Filipino martial arts were simply practical adaptations to the prevailing environment at the time, which weren’t recorded and cannot be recreated from our modern perspective.

The De Campo Difference: Speed and Efficiency

With regards to the specific system in question, De Campo Original 123 devised by GM Jose Caballero, while much is well-known, other aspects are not documented or are unknown, even to his sons, relatives, and former students. For instance, GM Caballero devised his curriculum and opened his school in 1925 when he was only 18 years old. His descendants and students suspect that he had training in FMA, perhaps through a co-worker. He was also known to closely watch the stick contests at various local celebrations from an early age. Although the basic curriculum and description of the system have come down to the present intact, a clear connection to other systems has not been found, to my knowledge.

In addition, although GM Caballero earned his fame by documenting his 10 consecutive wins in stickfighting contests, the system seems to be based on a bladed, rather than a stick, system, as many references to blade techniques can be found. What makes his system unique is his ability to identify specific components of movements that can speed up or slow down the interaction. By way of comparison, two sprinters could have identical speed, but if one can get out of the blocks a tenth of a second faster, they are always going to win. GM Caballero’s system illustrates many shortcuts to better stick management and movement not typically found in other systems, which would be very useful in a one-on-one stickfighting contest.

A Living Legacy and a Personal Journey

The De Campo Lineage

Although GM Caballero flew under the radar for many years, he did in fact teach his systems to many of his family and friends. Several of his sons are or were well-versed in the system, and his grandson, Jomalin, living in the Philippines, is currently the heir to the system. In addition, several of GM Caballero’s students and their descendants teach their own versions of De Campo based on their own experience, incorporating other types of FMA. Ireneo Olavides, who won a stickfight trained by the GM, has a system called De Campo 123 IO. Another system is called De Campo PPZ. And the Lameco Eskrima of the late Edgar Sulite is well-known for its extensive incorporation of De Campo 123 Original techniques in its curriculum.

A Personal Quest for the Source

One should also be aware that unrelated FMA systems may incorporate the word or words “Campo/De Campo,” which simply refers to a field, e.g., the countryside. GM Caballero passed away in 1987 and, here in the States, might have remained unknown if not for the influence of his former student, Edgar Sulite. For my part, after the passing of Edgar, I decided to search for De Campo to see if the system was still extant, which it is. Presently, I am affiliated with a system out of the Philippines called “De Campo 123 International,” which has an extremely well-documented and concise explanation of the original system that won’t be found anywhere else. For anyone interested in FMA, a lifetime of useful material can be found online, provided by Paolo Pagaling, the administrator/founder of this particular group, as well as live Zoom sessions with certified instructors. There is no ranking system. A practitioner can become certified as an instructor by completing the requirements and with the consensus of the other instructors.

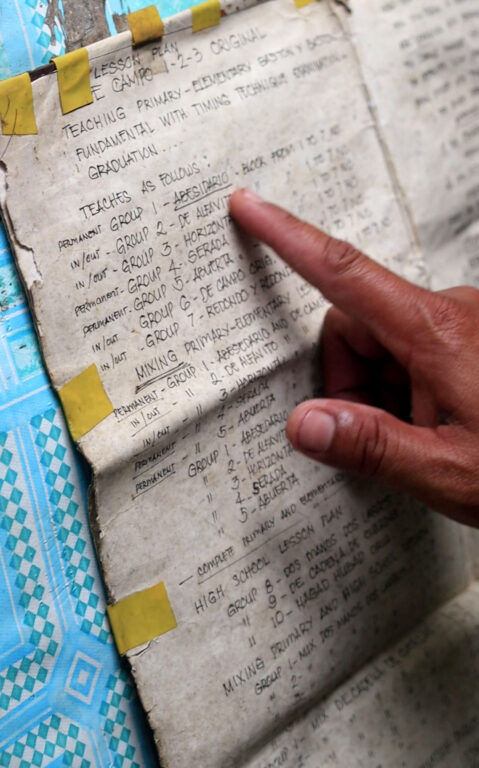

Inside the Curriculum

The system is strictly long-range with footwork intended to guarantee the safety of the fighter. In basic terms, only two stances are used: front-loaded and back-loaded, although the footwork requires much practice. Emphasis is placed on the hayang-kulob (supinated-pronated) hand position and the bicep tap/push. Techniques include single-stick, double-stick, and bladed applications. The three sections of the basic curriculum are: 1) Elementary, with seven elements; 2) High School, with three elements; and 3) College, which are seven striking techniques. At the advanced level, thirty Specializations incorporate the seven Specials. The entire basic curriculum, handed down intact from 1925, can be completed in 45 minutes once learned thoroughly. Although seemingly simple, much practice is required, both contact and non-contact, to achieve competence. This system has been an extremely useful addition to my overall knowledge of both FMA and martial arts in general.